On A Motherless Mother’s Day, Remembering to Heal and to Laugh

You wanted to know how I am—meaning since my loss, since my mother died. I say, “doing okay,” because sometimes I am okay. Sometimes I forget, and life feels normal. I say, “You know, it comes in waves,” meaning grief comes in waves, meaning sometimes it’s sharp and sometimes it’s dull and heavy and sometimes it lifts into nothing.

You wanted to know how I am—meaning since my loss, since my mother died. I say, “doing okay,” because sometimes I am okay. Sometimes I forget, and life feels normal. I say, “You know, it comes in waves,” meaning grief comes in waves, meaning sometimes it’s sharp and sometimes it’s dull and heavy and sometimes it lifts into nothing.

“Doing okay. You know—it comes in waves.” It is a comfort to me to say this because it sounds healthy. I am being honest, real, but not falling apart. I mean to reassure you. Friends like you distract me, which I appreciate more than you can imagine. Work distracts me. Other people’s lives and problems and needs distract me. If I couldn’t work, if I couldn’t listen, I wouldn’t be back. But I can so I am.

I’m being honest because you asked in a way that I trust. I can tell you care. A lot of people care, a shocking number of people care, which is nice, but which overwhelms me, makes me feel guilty because –What if I forget to acknowledge your caring? What if I forget to express my gratitude?

Because I am forgetting a lot lately, forgetting to manage the things I normally manage with little difficulty, forgetting what day it is. Forgetting who has to be driven where and picked up when and who just saw the orthodontist and cannot eat anything hard for a few days.

Sometimes, like I said, I forget she’s gone. I think I just haven’t called her yet today, that she’s still in her apartment in the city and later, when I’m out walking the dog, I’ll give her a call. Sometimes I do pick up the phone to give her a call. And then I remember.

Sometimes, of course, I am not okay. You know that, I’m sure. Because when I say it comes in waves, meaning grief, I’m referring to the surges. There are times when the weight in my heart is so heavy I cannot remain standing, and collapse on my kitchen floor, literally. I make sure one is around then but the dog, who comes and licks my tears away. Sometimes, there are too many tears to lick, and my face winds up a swimming mess of sorrow and dog drool.

Sometimes I think: how is it possible for me to be here on this earth, when there is no longer her? She has always been here in my life, since my first breath. Before.

And there is the sadness about my father too—whom we lost twenty-three years ago. Not that I’m mourning him again, just mourning them together. My parents as a unit. Of our small family—just us three—no one is left but me.

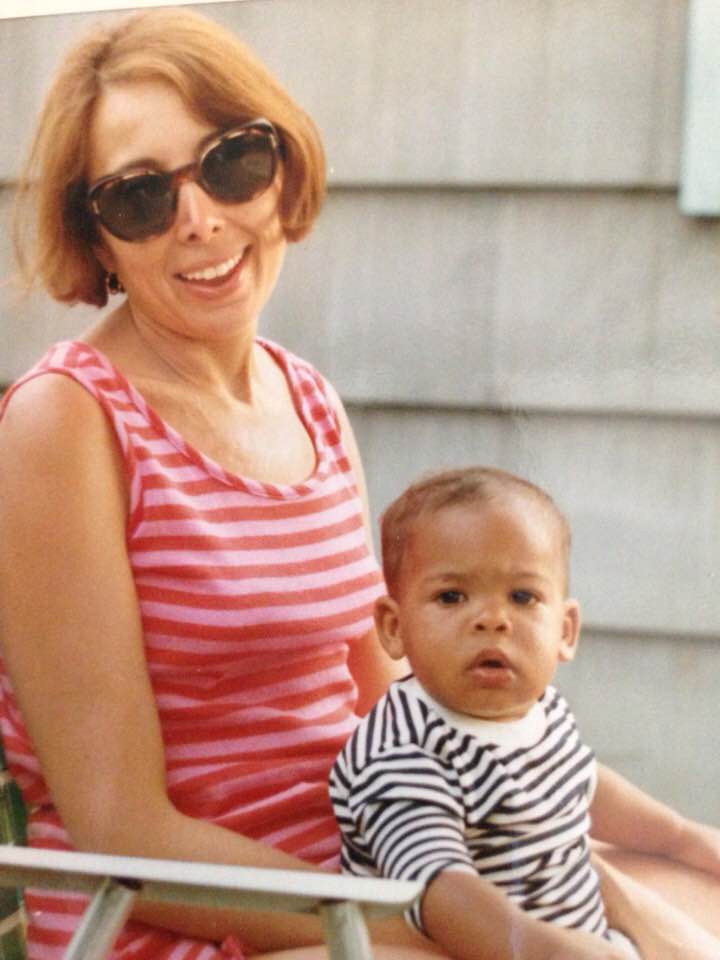

Still, I am lucky. I have so much of them left: photographs, manuscripts, letters, mementos. Works of art that Dad created with Mom as his muse. A book about Brooklyn that Mom wrote and Dad illustrated for the children in one of her first-grade classes.

My mother was a story teller, as you well know. Over the years, she’s told me the stories of their life together before me. The sixteen years that they were Mel and Lorraine, before we were The Williamsons. In recent weeks, going through her apartment, sorting her endless things, I’ve unearthed boxes photographs that accompany the old, before-Lisa stories. One crumbling envelope reveals the trip to Maine where there were fresh blueberries and cream every morning. Another holds their trip up the coast where they tried to cook out on the beach and were assaulted by bees. Here are the gatherings at their first apartment, in Flatbush. Lola and Sam’s wedding. A waiter at the Vanguard in 1951.

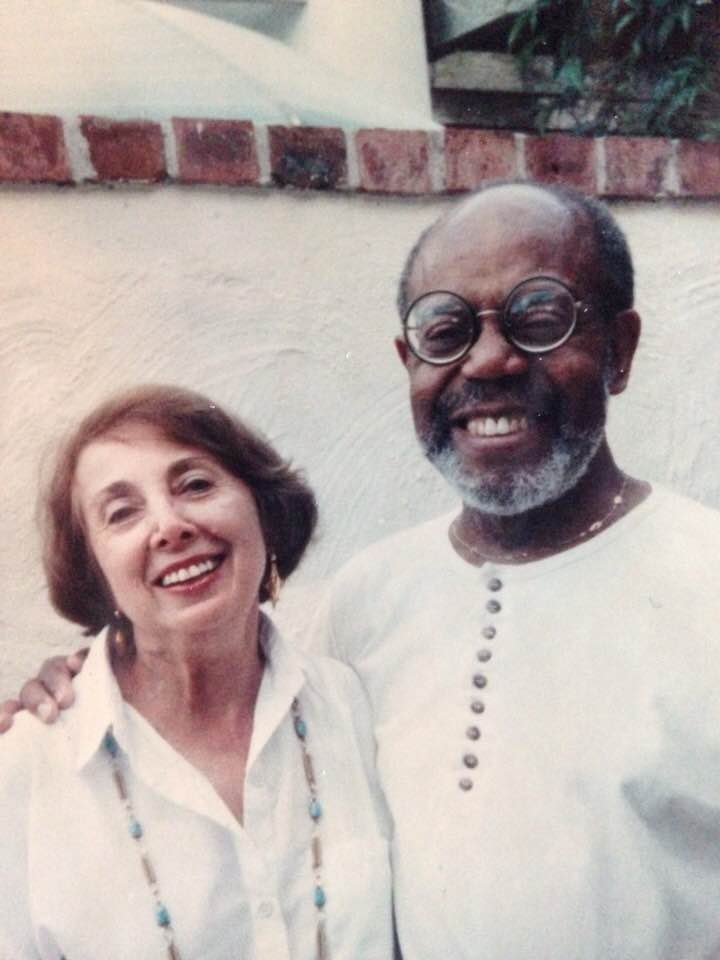

My favorite photograph is a later one from a trip to Barbados when I was already out of college. This is how I remember them best together, smiling, free to enjoy one another and life. And me. I make an imprint of this image on a scrim inside my mind, bringing it up during those moments when I need them.

imprint of this image on a scrim inside my mind, bringing it up during those moments when I need them.

The thing about death is this: You say good bye if you are lucky enough to have the chance. A week goes by and you realize, “I haven’t seen her in a week.” A week after that it’s, “I haven’t seen her in two weeks.” And the time since you’ve seen your loved one stretches out longer, longer, all the way to forever. Forever seems devastating at first, but you get used to forever. I learned that when I lost my father. Ultimately, your heart stops stinging, and the memories and photographs sooth you, lull you to a place of wistful acceptance.

I’m used to missing Dad. I’ve had decades to practice. Mom is harder because it’s been just a month—no, two months. The missing is deep right now. Her absence is everywhere I turn. So, I sit here, at night on my sofa, beside the sleeping dog. I close my eyes and bring up her image. Her smile is wide enough to wrap myself in, warming my shoulders, soothing my pain. Now I summon the sound of her laughter, which began with a snicker, leading to girlish giggles or whooping guffaws, one shoulder often bobbing up and down. It was contagious, never failing to set me off. Laughing with her—that’s what I’ll miss most.

Today, I’ll make sure to laugh with my own children and carry on her legacy.

Wishing you a Mother’s Day full of Laughter and Love