Apartment #17D – An Ode

This is the site of my childhood. Notches on a closet doorway mark my growth. Outside, on the balcony, a dark stain on one brick betrays the spot where Teenage Me hastily stubbed out a cigarette as I saw my father approaching. This apartment has seen my first steps, heard and felt an ocean of my tears, witnessed my friendships and my loves—wholesome, thrilling, sometimes toxic. I said my last goodbye to each of my parents here. For Dad, that was twenty-three years ago. For Mom, it’s been two months.

This is the site of my childhood. Notches on a closet doorway mark my growth. Outside, on the balcony, a dark stain on one brick betrays the spot where Teenage Me hastily stubbed out a cigarette as I saw my father approaching. This apartment has seen my first steps, heard and felt an ocean of my tears, witnessed my friendships and my loves—wholesome, thrilling, sometimes toxic. I said my last goodbye to each of my parents here. For Dad, that was twenty-three years ago. For Mom, it’s been two months.

And now I face the task of packing up, clearing out, cataloging the pieces of our history. The estate sale “specialist” broke it down for me. Everything—every thing—can be placed into one of four categories: Sell, Donate, Trash, and Keep. A simple formula. But wherever I turn, something indispensable catches my eye: An ancient datebook, a ring, the sort of icepack they no longer make. A telegram sent in 1947—my father assuring his mother that he had arrived somewhere safely. I have no idea where or how to start.

We were the Williamsons—Dad, Mom and me. The only family who has ever lived here. Mine is the only childhood these walls have held. The building went up in the late fifties, part of a complex of four red-brick structures with one- and two-bedroom apartments to rent. My parents chose one above their means at the time: A two-bedroom at the end of the hall on the seventeenth floor for two hundred dollars a month. It looked out on the corner of One Hundredth Street and Columbus Avenue, boasting a balcony from which you could see Central Park if you craned your neck. From the dining room window, you had a red-and-orange steam-bath of a sunset in summer; cool, lavender twilights in winter. From one spot behind our dining room table you could gaze past rundown church steeples and the dingy sides of housing projects to catch a glimpse of the Hudson River. Everyone who visited would remark on the view I took for granted.

It took cunning to rent such a place back in the nineteen-fifties. My parents had a system for apartment hunting. Mom would view each place by herself, my father’s long list of preferences and aesthetic requirements in mind. Dad knew about real estate. His parents had owned two homes back in Chicago: One that they rented out, and one where they lived with their sprawling family of children and grandchildren. But Dad could never accompany Mom to view any apartment until she had signed a lease. To rent the apartment of their dreams, my mother needed to present her prime qualification: whiteness. Her husband, she would tell the building manager, was at work—which was true. What was also true, but what she didn’t share at this point, was that her husband was black.

Mom and Dad moved here ambivalent about children, but not entirely opposed. When they wed in 1950, friends who were interracially married and parenting mix-raced children didn’t recommend it. Their kids were picked on at school, accepted by neither the black kids nor the white kids. No. Best leave well enough alone and enjoy one another without children. My mother was a teacher, surrounded by kids all day long. She claimed that she had no need for her own. Her work taught her all the things that can go wrong with children, the risks of illness and disability, the emotional turmoil they could face in the best of circumstances. Best not, she agreed with my father. Best enjoy the children of friends, to be God parents, to be free. Then Mom turned thirty-nine and changed her mind. “I want one,” she told him. “I want my own.” “Let’s have one then,” Dad replied. And crossed his fingers, hoping for a girl.

Their kids were picked on at school, accepted by neither the black kids nor the white kids. No. Best leave well enough alone and enjoy one another without children. My mother was a teacher, surrounded by kids all day long. She claimed that she had no need for her own. Her work taught her all the things that can go wrong with children, the risks of illness and disability, the emotional turmoil they could face in the best of circumstances. Best not, she agreed with my father. Best enjoy the children of friends, to be God parents, to be free. Then Mom turned thirty-nine and changed her mind. “I want one,” she told him. “I want my own.” “Let’s have one then,” Dad replied. And crossed his fingers, hoping for a girl.

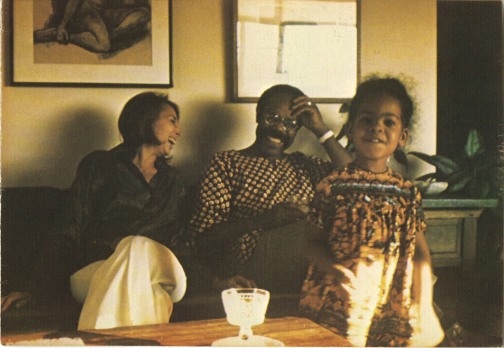

Here is another box of photographs, starring me as a newborn, an infant, a toddler. It happened easily considering their ages, the pregnancy, the birth, though my early months were marked by colic. No one slept much until I was at least a year old. But in the pictures of that year, my parents’ faces betray nothing of the challenges, only the joy. In me, in one another, in the life they’d made from scratch. Together they created a joint culture in our home, made of art and music and books. Made of black and Jewish heritage, made of Chicago and New York and Louisiana (from his parents) and Russia (hers). And that was our place.

“You just need to decide what you want,” friends have said. Just. A word offered to simplify, minimize the effort involved. These friends have been supportive, accompanying me to my mother’s place (it hasn’t been Dad’s for twenty-three years), they have washed, folded, tossed and recycled, and again and again, held up some vase or salt box or kitchen tool, eyes questioning.

As my friends exhume relics of our life, as they dust, shine, wash and dry, our dining room table fills with the mismatched decorative pieces—Dutch cookie jars, Egyptian Scarab beads, and Senegalese wooden masks—looking like a life-raft packed with strangers thrown together after a shipwreck.

But through the chaos and clutter, I still see us three, sitting here: Mom to my right, Dad to my left at the head of the table. They trade sections of the New York Times, talking politics over my head.

“That S.O.B.” My mother says, which I know means Nixon. She begins to read aloud, but Dad cuts her off.

“You see? You see?” He sets down the second section of the paper to drum an index finger on the table. “This is the kind of thing I’m talking about.”

It was part of an ongoing discussion in which terms like race and fascism and civil rights were thrown around. When the discussions were too

It was part of an ongoing discussion in which terms like race and fascism and civil rights were thrown around. When the discussions were too intricate, the words became a soft, spring rain on my shoulders, nurturing, soothing. Because even as they ranted, their joint indignation would keep me safe from whatever evils were out there. It’s what I believed unequivocally.

intricate, the words became a soft, spring rain on my shoulders, nurturing, soothing. Because even as they ranted, their joint indignation would keep me safe from whatever evils were out there. It’s what I believed unequivocally.

What do I want? I want my parents back. Of course. But I’ll settle for the obvious things, like my mother’s photo diaries, my father’s memoir, his unsold screenplays, his short stories and articles. The sentimental things. My father’s Panama hat—straw with a colorful pink and green band. My mother’s gold chain belt from the seventies. I want the photographs with all three of us together, but also the ones that predate me, documenting those first sixteen years of their marriage. My parents, living it up at the Vanguard in 1952. With friends on the Maine coast in 1954. I want the photographs that date back even further, to the years before they met. My father at the back row of Class 5B at the Willard School. My mother and her little sister at the 1938 Chicago World’s Fair. Dad in the army, Guam World War II. Mom as the Queen of Hearts in the University of Illinois Hillel Stunt Show, 1945.

Time is running out quickly. The place must be emptied by the end of the month. My parents are gone. I live with my husband and children in another state where we are rapidly accumulating our own memories. It’s time for this apartment to hold someone else’s stories.

There is healing in the going-through of my family’s past, in touching each treasure, each building block of our existence. In both hands I cradle a stone water-buffalo that my mother acquired on a trip to China. I breathe life into it for one final second, then set it down for good.